THE GAA COMES TO LOWER DRUMREILLY – Fr. DAN GALLOGLY (RIP)

*This article has been reproduced from the booklet commemorating the opening of the Aughawillan GAA Park in May 1982.*

THE tradition of native games in the parish of Lower Drumreilly goes back long before the establishment of the GAA to when crowds played cross-country football between Ardmoneen and Drumbibe. This rough and tumble game was played with a ball made from a ‘scoith’ or sprat rope rolled into a ball. It lasted all day and the only prize was to bring home the ball. This was the symbol of victory.

The GAA reached to Leitrim in late 1888 or early 1889, some four years after it was founded in Thurles. Large sections of the population were then in a state of semi-starvation caused by a series of bad harvests that hit the potato crop on which the majority of the people of the county were still dependant. Agricultural prices were depressed by an influx of cheap American products, particularly grain, on the European market. People were unable to pay their rents, no matter how moderate. The result was evictions and an increase in agrarian crime by the Ribbonmen. ‘Captain Moonlight’ again roamed the hills of Leitrim.

In August 1890 blight hit the potatoes for the second year in succession and it rained for almost two months. The Sligo Champion reported from Manorhamilton on 4 October that the uncut corn was rotten in the ground and that the potatoes where they were not rotten were small and ‘swimming in water’. ‘Every furrow has its miniature flood, every hollow spot is converted into a pool.’ wrote the Champion. It went on to pose the question, ‘What are the people going to do? to starve and die as in ‘fortyseven, is it?’ In the south of the county half the potato crop failed and most of what was harvested was unfit for human use. Farmers were forced to sell off their pigs as they hadn’t enough potatoes to feed them. The result was a glut of pigs on the market and a collapse in prices. A public meeting, chaired by Fr.Dommick McBreen, PP, Ballinamore, was held in the courthouse in Ballinamore to protest about the state of the people and to demand public works to alleviate their plight. It was claimed that 10.000 people in south Leitrim were on the verge of starvation and amongst the townlands worst hit were Aughawillan, Corduff, Corramahon, Drumreilly and Glennanbeg.

In December seven families were evicted from the townland of Stroke on the Marsham estates and their houses burned to the ground by Marsham’s agent, Mr Hewson of Donegal, backed up by a large force of police. This sparked off what can be described as the Stroke land war which featured one of the longest boycotts on record in the county, lasting for almost twelve years. A local balladier captured the scene at the Stroke evictions as follows:

‘The cries and sobs of those widows and orphans

When they saw their homesteads all in a blaze

It would rend the heart of a human savage

On these poor creatures for one moment to gaze.’

To ensure that the evictions would be a success emergencymen were introduced by the agent, Percival, McGurdy and Davis. All three were setup in the parish with police protection. There followed a twelve year boycott on them until they were forced to leave. They were followed to fairs and buyers were warned not to buy their cattle. When they cut turf, it was, thrown back into the hole that night. Their cattle were stolen. Business people refused to serve them and they had to be supplied from the police station. The boycott was the subject of a number of ballads heard until recently in the area – all of them immortalising the emergencymen as objects of popular hate – ‘Garadice Emergencymen’, ‘Emergencymen’s Jennet’ and perhaps the best known of all, ‘Percival’s Mare’. The latter, in the form of an imaginary dialogue between Percival, his Mare and Captain Moonlight, tells how Percival’s valuable mare was taken away, never to be found, by Captain Moonlight’.

‘Countrymen, dear countrymen, to you I now declare

On St. Patrick’s night by the moonlight I lost my darling mare.

You know it is a great loss to me, with that I do abide,

Oh was it Captain Moonlight or was it suicide?

She said to me the other day she (mare) could not understand

Why she should work for me all day on other people’s land

Some of whom have crossed the main to earn foreign bread

When going left their curse on me and prayed I might be dead.’

During this period of crisis the people found a spokesman in Fr. Patrick Gilcreest, the local parish priest. His advice, given at after-Mass meetings held outside Coraleehan church, was listened to and acted upon. He endeared himself so much to the people that when he died many years later as parish priest of Laragh, Co. Cavan, numbers of them travelled to his funeral. During the 1892 election campaign Fr. Tom McGovern, CC, Ballinamore, himself a native of Corlough, recalled the Stroke evictions in an attack on landlordism at a public meeting in the town:

‘Remember the seize of Mr. Prior’s house in Crimlin. Remember Tarmen! Who burned Pat Prior’s house in Tarmen? (shouts of Cooke, Cooke). Remember Stroke. Who burned the houses in Stroke? (cries of Hewson of Donegal fame). Here we have a whole townland reduced to a desert—seven families evicted, their houses burn…’

He went on to outline the fate of evicted, Michael (Mickins) Dolan, who was evicted because he owed four years’ rent. He got twenty pounds from Australia and was able to make up three and a half years’ rent He got back his farm and his neighbours helped him put in a crop which failed. His father died and this involved him in further expense. He was served with an ejectment order again and took his last cow to the fair in Blacklion, but she died on the way and arrived back with 2/6, the price of the hide. He was evicted again, but re-entered the house. The emergencymen set fire to it at night and he himself and two of his children were nearly burned.

It is against this background of semi-starvations, evictions, moonlighting that the GAA was born into Lower Drumreilly. It spread rapidly south of the county in the first half of 1889. On 14 April a county board was established, chaired by Tom Fallon. It had nineteen affiliated clubs. On 26 October the county convention in Drumshanbo was attended by representatives of 21 clubs – all of them, except Killanummery, from south Leitrim. Lower Drumreilly John Dillons were represented by P. Dolan and M. McGovern. Along with their near neighbours, Oughteragh Wolfe Tone (Cornawall) they were seeking affiliation which had been refused them at an earlier meeting of the county board. According to the rules of the GAA there could only be one team in a parish. Ballinamore William O’Briens were objecting to the affiliation of Wolfe Tones. They looked down on their country neighbours who, incidentally, also had players from Coraleehan, and referred to them as the ‘Cornawall puckbags’. They had the backing of the parish priest Fr. Dominick Mc-Breen, who wrote saying that one team in the parish was enough and that he had good reasons for saying this. Phil Gaffney and Pat Flynn, the Wolfe Tone representatives, were adamant that ‘they would never play with Ballinamore’. John Dillons were being refused affiliation for slightly different reasons. They had no branch of the Irish National League in the parish and as well they had a land-grabber on their committee. When their application was refused at the convention both their delegates became turbulent and the chairman, Denis Cassidy, told them that they were a disgrace. There was a second team in the parish at the time, Lower Drumreilly Rory O’Donnells, drawn from the Aughawillan area. Later, both John Dillons and Wolfe Tones were both recognised by the county board.

Twenty four teams took part in the first county championship held in 1890. The county was divided into four divisions The Ballinamore division included Ballinamore William O’Briens, Fenagh St Caillins, Oughteragh Wolfe Tones Drumreilly Upper. Charles Kickhams Drumreilly Lower. John Dillons Carrigallen Mandevilles. On 22 June, Ballinamore and Mohill Faugh a’ Bealachs met in the first ever county final played on the shores of Lough Scur near Keshcarrigan The field was hilly and uneven and the part near the lake was wet Despite bad weather crowds were winding their way towards Kesh from early morning:

‘The fearless St Caillins and dashing Rory O’Donnells (Aughawillan)

The gallant Wolfe Tones and fearless Dan O’Connells (Cloone)

The youthful William Redmonds (Kiltubrid) and mighty Connaught Rangers (Drumsna) The star of all, Brian Boru’s (Gorvagh) and many other strangers’

The curtain-raiser was a challenge between Lr. Drumreilly John Dillons and Kiltubrid Redmonds. The Roscommon Herald described the play as follows:

‘As far as tumbling, collar and elbow (wrestling) and tripping… shouts of “lift the ball”,

“referee here, referee there”. The outsiders were the touch-lines and in the end the

ground was as narrow as Jimmie Lawder”s railway (narrow gauge)’.

The story of the county final proper belongs elsewhere except to say that it was won by Mohill, who became the first county champions. Rory O’Donnells did not take part in the championship, but later in the year they held a very successful tournament in Drumarigna. Seven hundred people enjoyed challenge games between Oughteragh Wolfe Tones, Keshcarrigan Redmonds, Up. Drumreilly, Kickhams and Carnck Robert Emmets. The Anglo-Celt commented ‘that the Cavanmen who were members of the Rory O’Donnells side deserve praise for excellent play.’

The coming of the GAA brought excitement and pageantry to a rural community that had been buried in depression and known any form of organised sport, especially field games. It gave them something to talk about, something to shout and boast about and even on occasion something to fight about. It cemented parish boundaries and developed a sense or parish pride hitherto lacking. People were now proud to belong to a particular parish. John Dillons practiced sometimes in Coragh bottoms and sometimes in Moher. Incidentally, there is a tradition of a team in Moher drawn from the townlands of Coraleehan that are in Co. Cavan and that this team played in Cavan. It probably belongs to a slightly later period and was a result of a political split in the area. The ball was homemade from the hide of an ass. The hide was dried and the hair burned off it with lime. Three pieces, about the size of a large plate, were cut out of the hide and sewn together by a local shoe-maker. It was then stuffed with rags or hay or inflated with a pig’s bladder whenever one was available. I am indebted for this information to Charlie McTague of Drumcromman. Tournaments which were simply a series of exhibition matches played on a single Sunday brought great excitement to an area. The band always travelled with the team and the team marched on to the field led by the band. Often as many as four bands competed with each other between games. The Coragh Fife and Drum Band travelled with John Dillons. With 21 – aside in a field less than half the size of a modern field and kicking a bad ball, without any tradition of team games, it was natural to expect arguments, and sometimes hostilities. Things were further complicated by family and political that were carried on to the field. The 1890 convention found it necessary to introduce by-laws controlling ‘roughness, jumping on an opponent’s chest, violent shouldering, tripping (hand and foot), collar and elbow (wrestling), playing the man instead of the ball’.

The GAA in Leitrim died with the Parnell split in 1891 and remained moribund until 1904 when it was revived, thanks to the initiative of Mohill. No team from Lower Drumreilly took part in the 1904 championship, but the Anglo-Celt reported a challenge between Aughawillan and Aughsheelin at Mondra Park for a prize of one pound. The records for the 1910s are very scrappy leaving us no account of the fortunes of the game in the parish.

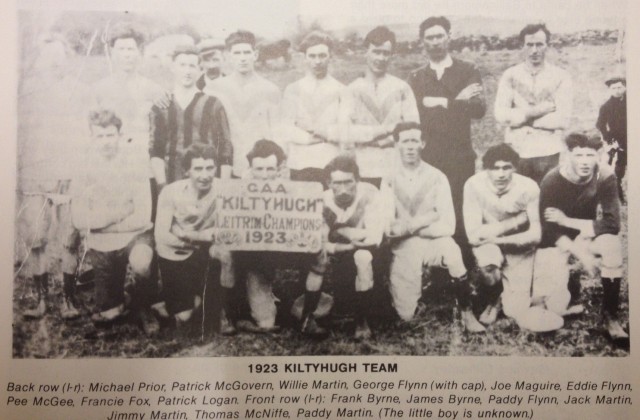

The 1920s was the golden era of Kiltyhugh. The county board was defunct during the Civil War. It was revived at a small meeting held in Gorvagh in March 1923 while the Civil War was still on. Tom Kiernan, Fenagh, was appointed chairman of a small committee charged with organising a county convention which was held in Mohill. It was attended by representatives of Gorvagh, Mohill, Fenagh, Cavan (Eslin), Lower Drumreilly, Aughavas. It was eventually won by Lower Drumreilly, who defeated Mohill, Cloone, Ballinamore on the way.

The 1923 championship has wrongly attributed to Upper Drumreilly in some of the official lists of title holders and in 1976 Aughawillan were talked of as the first team from the parish ever to win a senior county championship. While the team was affiliated as Lower Drumreilly, it was best known as Kiltyhugh. It was backboned in the ‘twenties by the Flynn – Tom, Willie, Eddie and Paddy – the McTagues and the Martins. Fr Pat McTague was reckoned one of the best footballers of his era in St. Patrick’s College, Cavan, and was placed in the same category as a college footballer as Big Jim Smith of Cavan. He played at centre field for Leitrim in 1925. His football career was cut short by the fact that he was studying for the priesthood. The Flynn brothers also represented Kiltyhugh on the county team at different times – Tommy in 1925 before he emigrated to America, Willie won a Connacht championship with Leitrim as a corner forward in 1927. Tom Flynn returned as a New York player in the Tailteann Games of 1928. The Martin brothers, Willie and Paddy, although natives of Templeport, also played for Kiltyhugh. Willie was on the Leitrim team for a great part of the ‘twenties, also winning a Connacht championship medal as a half-forward in 1927. That same year Paddy won a Junior All-Ireland with Cavan. Willie Martin and Ballinamore’s Ned Dolan were the first Leitrim men to be honoured with a Connacht jersey.

Immigration began to make itself felt in the late ‘twenties. They were reduced in the ‘thirties to junior status and survived down to 1937. During the ‘twenties and ‘thirties two other Coraleehan men were making their names elsewhere, Sean O’Heslin and Seamus Giiheaney. O’Heslin was in goals tor Cavan in the All-Ireland semi-final in 1923, which they lost to Kerry by a disputed point. When he came to Ballinamore he did more than anyone else to organise the club and to build a great tradition on which the hopes of many a good team from his native parish later perished. He was also secretary of the county board and a member of Connacht Council. Seamas Gilheaney went to work in Cavan in 1917 and served Cavan football down to the 1960s as an administrator. He was chairman of Cavan County Board when they won their first All-Ireland in 1933. His last big contribution to Cavan football was the organisation of Bord na Scol in the 1960s, which took charge of under-age football in the county.

Today, on the occasion of the official opening of their new park, the people of Lower Drumreilly can look back on an unbroken tradition of loyalty to our Gaelic games going back to the earliest days. They can feel proud of that tradition and of the people who built it in hard days of economic depression, emigration and political change. The fine park which is being opened today is a monument to those who have gone before, a tribute to the courage of the present and an act of faith in the future.